by Jonty Watt

One of the more exciting projects to come out of RAM recently was Mia Serracino-Inglott’s performance of her own composition at the Southbank Centre, titled Five Period Songs. Mia is a mezzo-soprano who regularly performs and creates new music, and who is challenging conventions of what it means to be a classical singer. While at RAM, Mia has devoted much of her time to working with composers and has featured in many world premieres (including a leading role in Louise Drewett’s opera Daylighting in 2022, and as soloist in two compositions in the Academy’s bicentenary ‘200 pieces’ project). It was clear to everyone in attendance that this is an artist for whom collaboration is vital and natural. I spoke to Mia to discuss this project, and her life as an artist more generally.

Can you tell us a bit more about Five Period Songs, and how you came to write them?

I was selected as one of six students for the Southbank Centre’s collaboration with RAM, called ‘Future Artists’ and run by violinist Daniel Pioro. Throughout the project, we spent four days working together – rethinking and moving away from scores, and generally finding new approaches to music-making. The end goal was to devise and create our own projects, and I decided I wanted to create a piece that focused on periods. The concept was to create musical and visual portraits of a day on your period, based on original artwork by different women. This became Five Period Songs for solo mezzo-soprano and ‘breathing performers’.

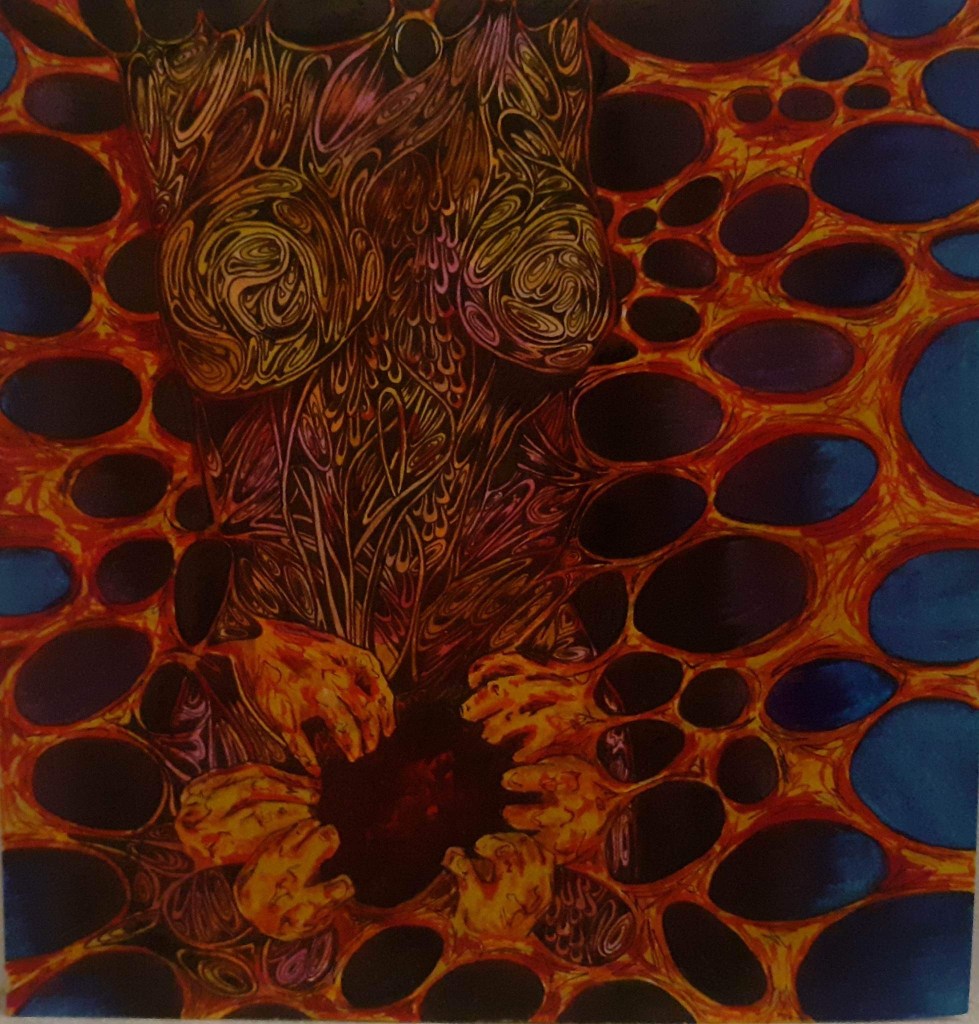

Can you tell me more about the artwork you used?

I knew that I wanted my project to be a collaboration with other creative people. I believe that kind of collaboration is vital in keeping classical music current and relevant. I contacted friends from RAM (including RAMpage team members Sena Bielander, Jess Anderson, and Ruby Howells) and two friends from school, Kate McMahon and Isobel Brierly-Croft, and they agreed to help. I didn’t give them any criteria at all: just to represent a day on their period. I wanted the challenge of interpreting whatever they gave me, and they ended up being incredibly varied. For example, Ruby’s was a set of graphs (which translated quite easily into music), while the others were more abstract – I had to respond emotionally to them.

Did you know from the start that the artwork would be so closely tied to your composition?

Well, I’m not a composer. The way I see it, I wasn’t composing a ‘piece’: I was just improvising based on prompts. The material was already there within the art itself, and I was lucky to have such fabulous material. I just extrapolated it into music. I’m fascinated by Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations; these are sets of instructions that generate musical pieces of unspecified length, and I was very inspired by them. In Five Period Songs, I wrote my own sonic meditation: the other performers were asked to ‘fill silence with breath’. This made the piece much more dynamic, with the breathing performers fulfilling the role of a Greek chorus accompanying my monologue. As for the singing, I gave myself short instructions – sometimes musical concepts like a certain scale, or vaguer ideas like ‘consonants’ and ‘pain’. I found this was enough to stimulate me to create something interesting.

I thought that the piece had a very nice overall shape to it, even though the art you responded to was so diverse. For example, Ruby’s was very funny, and Jess’s felt optimistic. With five different artists, you’re opening yourself up to all sorts, so how did you keep everything in check?

That’s what was so nice about it. When I set out to do it, it was all about ‘breaking the taboo’; periods are something that about 50% of the world experience, but you never really see them represented in art. In my head, I thought the piece was going to end up a real cry-fest, but I’m so glad it didn’t. Ultimately, it was about bodily- and self-acceptance, and that’s different for everyone, so it was crucial to show many different experiences. For some people, periods are awful and there is unavoidable pain. For other people, it’s a nuisance, but you can deal with it. I loved showing these different experiences, and in the future I’d be really interested in exploring this more. Maybe working with women of different ages, for instance, and young girls who have just got their period. I’d find that so fascinating.

You’ve alluded to the fact that you might expand the project. Do you have plans?

Well, I’m not a composer…

But you are a composer now!

I know, I’m still struggling with that. What am I now: a mezzo-soprano/composer? I don’t want people to think I’m only composing because I can’t sing as well as people who just sing. The structure of a conservatoire can make you worry about that stuff. But, in an ideal world (and when I get over myself), I’d love to expand on the project. I’d love to write something down that other people could use and appreciate as a written score.

As a creative person, how do you balance being a performer with your other interests?

We singers don’t usually get to interact with other departments – we have no chamber music assessment, for instance. I’m lucky because the composition department snapped me up very early. In a way, it’s all luck – I’ve worked with the right people. Being surrounded by people who want to create new things is very inspiring, and it enriches all aspects of my music. I sing so much contemporary music, then I go to sing Bach, and I’m the better for it. I understand myself better, as a person and a singer. Nothing creative you do will ever detract; it can only add.

It’s also important not to worry too much about whether what you’re doing is good. That’s something Daniel kept repeating: it doesn’t matter if everyone hates it! The question isn’t whether it’s good or bad. You’ve done something. If you have given a part of yourself to art – if you’ve not just scribbled something when you’re hungover and hoped people will like it – if you’ve given something of yourself to it, then it’s worthy. It’s art.

What advice would you give to anyone who feels in your position: if they feel an urge to do something that isn’t what they ‘should’ be doing?

Find your people. Find people who like the same things as you, whether that is baroque nerds, or people who just adore Schoenberg. If you want to do something, those people will probably want to do it too.